Archive for January 2008

California: The Problem in a Nut Shell — The Looming Crisis of Healthcare

The rising and unsustainable cost of health care inflation has prompted cutbacks in state funding of Medicaid in an assortment of states across the nation. I know this directly from my work with the government in Pennsylvania, and news reports from papers around the country indicate a similar experience. Yesterday, the state of California elected against pursuing Governor Schwarzenegger’s new health-care initiative – a modification of the approach undertaken in Massachusetts. Interestingly, a student in our executive program was one of the authors of this initiative. More interesting, still, a day later the state insurance commissioner vowed to strictly enforce the compensation laws, following a study indicating improperly denied and delayed payments by insurance firms.

Back in 1998, with my first quality improvement class, my students and I came up with a model for health care that has proven remarkably accurate. One of the items in that model was the recognition that the capacity constraints challenges that prompted the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 would only grow increasingly worse as the boomer generation approached retirement. We predicted then that the inveterate cost-shifting between insurance and government-sponsored payers, which prompted the arrival of DRGs, the failed Clinton health-care plan of 1993, and the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, would increase in intensity – pitting government against the insurance industry. This is based on the realization that we were approaching the limit of cost reduction and efficiency improvements available to practitioners. Unable to squeeze practitioners further, finger-pointing between payers seemed a likely act of desperation. http://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-bonus30jan30,1,4329899.story?ctrack=1&cset=true This, however, was not the limit of our predictions with respect to health care insurance. We foresaw the arrival of high deductible plans, as a means of cherry picking those least in need of medical care. With subsequent classes, we became increasingly concerned that such plans would promote the death spiral of adverse selection for the insurance industry.

While a subscription is required to this Wall Street Journal article, the freely available introduction notes two tangent issues with the California initiative and its defeat. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB120165305949826973.html?mod=hps_us_at_glance_health .

The first item is the recognition that California represented a poor prospect for a Massachusetts-style initiative, due to the size of its indigent and uninsured population. The Massachusetts initiative requires health care insurance coverage by all who are financially able to afford it, while promising state coverage for those who are not. Given the size of California’s indigent population, the defeat of this proposal is understandable. This, however, suggests that relying on state initiatives represents an unlikely solution to the looming resource constraints crisis, because California is not the only state with a significant indigent and uninsured population.

The second item mentioned in this introduction is the recognition that the California initiative (like that in Massachusetts) does nothing to address the core causes for health care inflation. In fact, no initiative of which I’m aware directly determines the most significant drivers of health care inflation, much less attempt to constrain them.

Constrain them? Isn’t that the rightful role of the free market?

Absolutely, but healthcare is not a free market, where competition serves to increase quality while managing cost to the customer. Medicare, Medicaid, SCHIPS, state and federal coverage for government workers, local government contributions to augment indigent care, federal coverage of black lung and other special forms of workers’ comp cases, and government coverage of healthcare for the prison population, combined, exceed all other payer classes and account for more than 50 percent of healthcare payments in the US. Consequently, healthcare in the US is more akin to socialized medicine than a free market. And this has contributed the problems described above — an unintended consequence of the effort to do the right thing when Medicare and Medicaid were introduced in 1965.

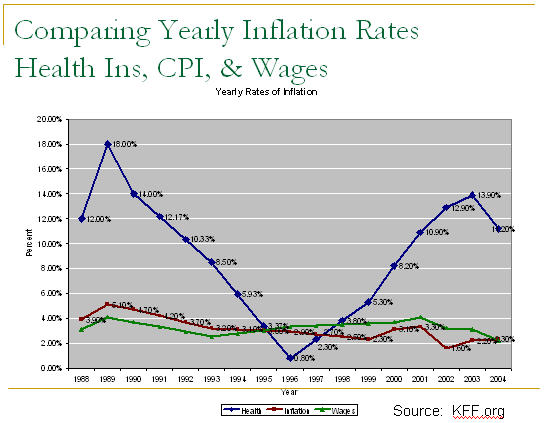

To graphically demonstrate the problem, here is a chart showing the year-over-year inflation rate of health care (blue line) in comparison to inflation within the United States (red line) and wage inflation (green line) from 1989 to 2004.

The previous chart, which indicates the yearly disparity between health-care inflation and wage inflation (the capacity of our customer to purchase our services), fails to provide a sense of the accumulated problem over time. Therefore, it is necessary to index each to 1989, in order to identify the cumulated effect.

The next chart, which extends back to 1981, indicates that, if health-care costs were held steady for the foreseeable future while wage inflation continued to grow along a regressionary trendline, it would take 61 years for wage inflation to catch up.

It is worth noting that the coefficient of determination (r-squared) for the wage trend line is greater than 0.99.

This is the problem we face. It is the reason government and the insurance industry seek to reduce payment to practitioners on a yearly basis. It is the reason the American people list rising healthcare costs as a significant political issue when they vote. And, surprisingly, no initiative by government has sought to identify and address the core drivers of health-care inflation. Less surprising, but disconcerting, nevertheless, no organization within healthcare has sought to do that which government has avoided.

Is it too late to address the problem? Well, the Boomer generation starts retiring in less than two years (some have already started early retirement). Our 45 million seniors of today will grow to more than 80 million by 2030, and Medicare is slated to go bankrupt by 2020. So, I’m not very optimistic. But I am open to your suggestions.

Related stories:

California Governor vows to continue effort: http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2008/01/30/MNHIUOK24.DTL&hw=Bill+%27over%27&sn=001&sc=1000

Article describing the defeat of the California proposal: http://www.latimes.com/news/local/la-me-health29jan29,1,1860303.story?ctrack=2&cset=true

Cost of Massachusetts plan expected to grow beyond $400 million: http://www.boston.com/news/local/articles/2008/01/24/cost_of_health_initiative_up_400m/

Halo Effect Review —

Last night, I came across this review of Phil Rosenzweig’s The Halo Effect: … and the Eight Other Business Delusions That Deceive Managers from Amazon.com. For anyone interested in management and with the study necessary to appreciate its references, this piece possesses uncommon depth, even with its abundant typos.

| By | Eggcrate “glodphlex” (New York City) – See all my reviews |

At the core of the Halo Effect is an impicit piece of mathematics, the Null Hypothesis. The Null Hypothesis has become a foundation of modern statistics, and Null has some very unfashionable things to say about human thinking. Null holds that we must assume that the universe is essentially random, and we will begin with the idea that randomness, or “noise processes” are the true explanation behind many seeming truths and meaningful coincidences. Only through rigorous analysis can we say that there is a probability (never a certainty) that other-than-random forces are at work. Thus we derive the notorious P-value, which says what is the probability that randomness alone *coulld not* account for the outcome ?

Business literature, it goes without saying, is a large and lucrative enterprise which must remain constantly in motion, like certain large fish, by grinding out a steady stream of “state of the art” theories, concepts, perspective shifts, novel vocabularies, often lending a patina of legitimacy to the New New thing which of course supercedes the Old Old thing.

Rozenzweig has scented the unspoken relationship between Business and Inspriational writing, and fundamentally identifies a deep strain of arbitrary, indulgent, and often opportunistic hawking of trivial intellectual novelties packaged as deep insight.

What Rozensweig is demanding his reader to do is “grab the right end of the stick” and not confuse causes with effects, or coincidences with good predictions. This message will probably not be met with much enthusiasm.

If much of what should work consistently, such as obsessive execution models, eventually doesn’t, and there is the inevitable regression to the mean of mediocre performance, what then does work ? What establishes critical perforative differences across business cultures ?

The answer, or a strongly partial answer might be found in Daniel Goleman’s writings, or the executive development at Goldman Sachs or innumerable papers and writings on psychology and behavior.

This essential distinction is self knowledge. From the materials emerging in many contexts, a very high, detailed, and thorough inventory of self knowledge which is consistently honed throughout the promotion ladder, and beginning as early in the executive’s career, will distinguish the brilliantly innovative, the ploddingly mediocre, and the catastropic miscast. This will, inevitably, have the greatest long term impact on the financial and cultural performance of the company. In other words, profit and the quality of the culture are inseparable, and the culture in general and the culture of self knowledge are equally inseparable.

The reason for this is that human behavior has two rough domains, the Proactive, when one is moving according to the established plan and is on a winning streak. We inhabit a culture that fetishizes the proactive stance, places a neurotic worship on “winning” above all else, and yet has an equally neurotic, unconscious disgust for the reactive stance, and “losing”. So, the executive is unconsciously, unwittingly socialized to be forever in the Proactive, Winning mode where he (or she) wears the magical Halo.

However, the Halo is also a crown of lead, because the status of “winner” positions this Halo wearing Proactive Winner into thought processes, behaviors, beliefs, attitudes to keep the Halo exquisitely polished and easily seen from a great distance.

In real life, once one has discarded the remains of infantile omnipotence and a lust for ego gratification at the expense of hard facts and amorphous, fluid realities, one is more ofthen that not forced into the Reactive mode.

Psychology teaches us that humans think and act very, very differently when the high control emotional state of Proactivity is shifted to the low control state of Reactivity, when the halo has to be taken off and melted down for ammunition, so to speak.

When one is then trapped in near-arbitrary linguistic distinctions of “winner” versus “loser” the mind will naturally regress to a more elementary, instinctual class of mental processes, such as obsession with detail and trivia at the expense of the big picture (a.k.a. paralysis by analysis), or cling to nuances and formalities (Freud calls this the narcissism of petty differences), or experience low grade paranoia and creative blockage, or fly into defensive rages, or generally behave in weird, irrational, and confusingly non-linear ways.

The smartest and hottest companies appear to have absorbed this lesson, they want to get under the skin of the Proactive, Winning, Upbeat Can-Do mindset and ask the brutal, vital, self preserving question, HOW does this candidate (for an initial hire, for promotion, for senior position) operate in the maximal reactive state ??? What instincts and unconscious resources does the individual, and collectively, the entire organization have on tap when the game changes, when one’s identity is under seige, when a disruptive technology or business model appears without warning ?

For this reason, and and all organizations with adequate resources should institute aggressive self knowledge programs with an emphasis on identifying the blind spot(s) of each candidate, and from that, providing them with clear feedback and counseling as to how those blind spots WILL, inevitable become the flashing illuminated signs in times of stress, change, or confusion.

The optimal strategy for a rapidly ascending Halo person, a perceived Golden Winner, a “savior figure” come to make it all right again, would be to go off site, away from the corporation, and engage the best, most candid psychological services available for a thorough multidimensional workup of all personal factors, with a particular emphasis on how one’s Defense Mechanisms shpape behavior and perception in times of stress.

Because of employment laws, there is only so much a company can do internally, with the 360 degree reviews, the Caliper tests, etc. all of which are useful withing the allowed limits of the workplace.

If Goleman is right, the seriously motivated executive, the one who will emerge as the long term winner, as opposed to the transient Halo wearer, will be the one who has had the most greuling inquiry into his or her failure modes and how this has formed the Operating Style.

If Goleman is further right, the greater the initial success, the lower one’s desire for self knowledge and self inquiry, especially painful, embarassing, or ego diminishing self inquiry,the more vulnerable he will be to “bolts from the blue”, and yet further studies have demonstrated that at the critical juncture of promotion, it is this very lack of self knowledge, fueled often by a hubristic arrogance (read: a measure of narcisitic personality disorder), that makes the executive drift from Proactive self confidence into Reactive Dysfunction, his or her loathing for self exposure and objective criticism may engender a defensive prickliness, or an avoidant withdrawal, or a paranoid rumormongering, all of which greatly undermine the holistic healthy functioning of the business organism.

In a phrase, this is the genesis of the long noted Peter Principle, one is inevitably promoted to the level of one’s incompetence, where one then remains for a long time, subtly but effectively clogging the arteries of the executive circulatory system.

How many senior executives have believed that they had everything under control, and the next day they find themselves pouring an extra drink and asking “what went wrong”? “how could we NOT see that coming”? “why didn’t anyone tell me”?

Sadly for the executive and his slaved over compensation package, what went wrong wasn’t a specific communication breakdown or ill structured policy, it was an endemic case of “Halo Fetishism” which should have been rooted out early on before the Peter Principle Effect became the normal operating mode. In a sense then the entire company, the enterprise, has to be not only intellectually alive to the world it inhabits, it must also be psychologically alive, it must embrace the HOW of its Reactive Modes, it must allow for lead halos as well as golden halos, it must learn to be comfortable with “negative emotions” such as depression and outrage, and learn to extract value from those not-upbeat-winner emotional conditions as vital sources of reality and internal feedback, and ultimately, worldly realism.

The alternative is obscurity, or worse, extinction.

The Outlier’s Power — Why We Emerged From the Caves

Why is it that we take statistics early in our studies? Well, there is a method to the seeming madness of our education, and, to understand it, it is necessary to recognize that logic, in its purest form, is mathematics. 1 + 1 = 2 is such a simple statement — demonstrably true — and so elegant in its evident correctness.

Within statistics, when you study multiple regressions, you encounter the concept of the “residual.” Residuals, by definition, are outlier events — those exceeding three standard deviations from the mean. Rare, by definition, they are the means by which the totality of humankind has advanced. Einstein was a residual. Stephen Hawkings is a residual. Mozart was a residual. Picasso, Ford, Roosevelt (FDR), Roosevelt (Teddy), Beethoven, Shakespeare, and Drucker were all residuals — outliers of excellence each. They were three standard deviations from the mean… anything but average… the tails in a Gaussian distribution. They were, in short, the means by which humankind progressed.

This is inordinately odd — contrary to all expectation. Heisenberg’s second principle of thermodynamics has it that everything tends to degrade over time; the truth of which is evident when comparing the image in the mirror to the senior class photograph from high school for any of us. Death, as an unavoidable reality, serves as both postulate and theorem, proving this great equalizing truth.

Despite this degrading recognition, we have emerged from the caves. We invented music and art and, most glorious of all, parenting. And all of this is predicated on the outlier. The average of humankind advances not because of the average advance or the average human, but, instead, because of the Eureka events produced by the exception and the exceptional.

It was, after all, a naked Archimedes, displacing water from his bathtub, who first uttered the expression “Eureka!” when discovering that, with water and its density-based displacement, he could measure the purity of gold and other precious metals. Of course, “utter” is too middling a description for the man who ran naked through the town, screaming “Eureka!” with the realization that he had addressed a long-standing concern of his king. At that instance, he could not know or appreciate that this moment of brilliance was a necessary predicate to international trade. Regardless of how you view globalization, we have the outlier of Archimedes to thank for it.

This is why the greatest human to grace the planet was not one of the names mentioned two paragraphs previous (Einstein, Hawkings, Mozart, Picasso, Ford, Roosevelt, Beethoven, Shakespeare, Drucker, etc.), nor was it Archimedes. No, according to a recent survey of noted historians, the most significant individual to promote the advancement of humankind was Gutenberg — the inventor of the printing press.

Before the printing press, the collective knowledge of humankind was reproduced by monks — sitting in their cloister, painstakingly scribing texts by hand. This process limited the distribution channel by which knowledge was available to curious and intelligent minds. Before Gutenberg, if an Einstein were born on some remote village, so what? No critical mass of prior knowledge would be available to educate and take advantage of such uncommon intellect. With the arrival of the printing press, all of this changed. Guttenberg’s invention became the LEXIS-NEXIS of that earlier time — the mass distributor of information.

Before Gutenberg, it would not have been possible for an obscure academic, at an obscure university in England, to achieve nearly instantaneous fame based on a single intellectual achievement. And yet, it was from this setting that, according to the London Guardian, the most influential book ever written was produced by a previously unknown and geeky little man.

His name was Isaac, and the year was 1687.

It was in that year that Isaac finally consented to the request of a friend to publish his thoughts on a small number of seemingly disparate subjects. From it, five great advancements arrived. Four of those advancements appeared within the text, and, strangely, the most important to come out of this effort was kept secret until some years later. The last of the four published advances was this:

F = G [ (m1 x m2) / r^2]

F is the magnitude of the gravitational force between the two point masses

G is the gravitational constant

m1 is the mass of the first point mass

m2 is the mass of the second point mass

r is the distance between the two point masses

This was the theory of gravitation.

The theory of gravitation hardly seems groundbreaking today, but it did resolve the argument of whether the planets revolve around the sun in circles or, alternatively, in elliptical orbits. The original mathematical resolution of this dilemma was derived from the fifth great (secret) advance — the one that never appeared in the original text. Specifically, answering this question of gravitation, alone, made it necessary to invent an entirely new form of math … calculus … a decade prior to its first publication by Leibniz.

Isaac, of course, was Sir Isaac Newton, and the other three great advances contained in his Philosophia Naturalis Principia Mathematica were the three laws of physics. I’m sure the you’ll recall them from your time in high school:

1. An object in motion tends to stay in motion unless acted upon by some net external force.

2. Force = Mass X Velocity

3. For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.

It is the rare and exceptional mind that advances us all, because it is the rare and exceptional that possesses a disproportionate influence when all is said and done. You know this as students, because you have taken tests. If you score 95% on four tests but score a zero on the fifth, your average is not 90% or 85% — despite the central mass of results in the 90s. Instead, this single outlier of a zero drops your average to just 76%. Pleasantly, since Gutenberg, the brilliant outlier has the same effect as the zero, but that outlier works in our favor, rather than against us.

It is an old canard that if you were to place an infinite number of monkeys, into an infinitely-sized room, seated at an infinite number of typewriters, eventually, one of them would hammer out Romeo and Juliet. Whether by design, genetics, inexplicable brilliance, or serendipity, the proportions work in our favor. Over 300 million merely-average Americans cannot negate the positive force of a single Dean Kamen — the inventor of the portable infusion pump, the Segway scooter, the fluorescent water purifier (being deployed in Third World countries), or that miraculous wheelchair that climbs stairs, traverses beaches, or raises up on two wheels so that the paraplegic can reach that can of soup at the top of the cupboard. Neither Al Franken nor Rush Limbaugh nor any other zealot, regardless of agenda or philosophy, can defeat the earnest but brilliant outlier, and the outlier arrives with sufficient reliability that ineptness and Heisenberg can be predictably defeated.

Good Idea? Chief Innovations Officer — Executive Pay and Status for Organizational Creativity

Should companies have a Chief Innovation Officer?

With all the excitement around corporate innovation as new paradigm to reach business’ differentiation and competitive advantage we have no full consciousness yet regarding the organisational structure that would support Innovation as a permanent function in today’s corporations.

Based in your own perspective would you justify the Chief Innovation Officer position to encourage innovation permanently in our organisations? If so, what could be a proper justification to promote such change in the manner on which corporate innovation is perceived, managed and developed?

This was the question posed by management consultant Octavio Ballesta on the professional and social networking site LinkedIn last week. Due to space limitations on that site, I am responding to this important question here.

Charles Manz (Professor of Business Leadership at the University of Massachusetts) and Henry Sims (Professor of Management and Organization at the Maryland Business School) published “The New SuperLeadership: Leading Others to Lead Themselves” in 2001 (ISBN: 1-57675-105-8). In it, they undertake an investigation of organizational leadership, asking the question, “what is the best way to cultivate effective organizations and teams?” In their text and other published papers, they draw on the precepts of performance psychology to identify the mindset and perspective of exceptional performers – which enjoys a rich history dating back to the Bobo doll experiments of Albert Bandura in 1961, where Bandura began investigating dysfunctional behavior as a benchmark of comparison for later research related to identifying hyper-functional psychology.

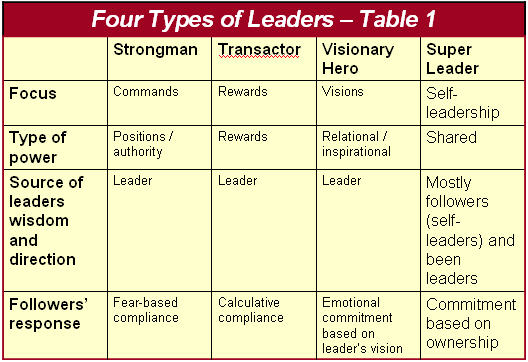

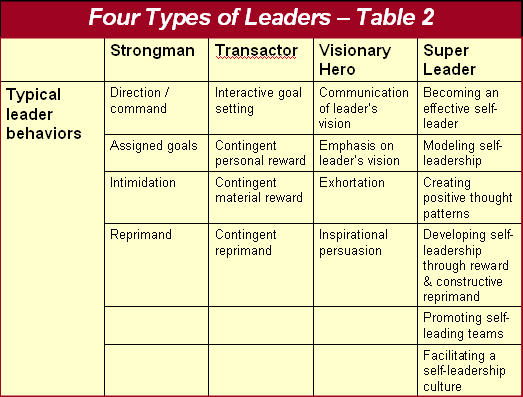

Manz and Sims divide the current leadership environment into four types: the strongman, the transactor, the visionary, and the super leader. The strongman relies on the issuance of commands and intimidation as the basis of his authority. The transactor, on the other hand, motivates through the use of incentives. The visionary, which is the closest of the four to the Chief Innovations Officer, relies on the workforce to adopt his vision for the future and to be inspired and motivated by it. Finally, the super leader understands the psychology of exceptional performance and trains his organization to adopt that psychology.

My purpose in describing this is not to urge the adoption of super leadership; although, I do believe the approach constitutes a superior model for improving organizational effectiveness and, from your standpoint as a consultant, a superior product offering for marketplace deployment. Instead, the purpose of this response is to consider the utility of creating a Chief Innovations Officer position. The problem with the visionary approach to leadership is, of course, that it requires front-line staff to buy into the leader’s vision with a level of personal commitment that may be beyond the average employee – whether the worker is tenured from before the transition or hired subsequently.

Under this model, the visionary would typically be the chief executive officer of the organization. As Manz and Sims note, it would be necessary to focus greater emphasis on selective, future hiring for external candidates and targeted promotions for internal candidates. This would move human resources into a greater position of power than is common in most organizations, making the Assistant Chief Innovations Officer the Director of Human Resources. This, in itself, would represent a significant cultural change, and, as we know, organizational change is one of the most difficult aspects of any firm to alter. Warren Buffett has famously noted that, “When a management team with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for bad economics, it is the reputation of the business that remains intact.“

Drawing on the work of Gallup’s Marcus Buckingham and his “Strength Finder” system, we know that we can identify and hire/promote for specific superstar capabilities, depending on the position and those skills that most reliably predict success within it. This would seem to support either of the two likely models for creating a Chief Innovations Officer position. On the one hand, we may seek to instill an innovations mentality throughout the organization, with every employee innovating. On the other hand, you may seek to extend the visionary model, where a single repository or small group are tasked with innovating for the larger organization. There are risks with both.

Under the first model, where every worker is an innovator, it seems likely that the firm will degrade into a state of chaos. Under this scenario innovation is abundant, every employee as an advocate for his or her innovation, and the firm degrades into a hydra-headed PushMePullYou of Dr. Doolittle fame – where innovative ideas arrive by the second but no advance follows in the absence of a targeted deployment of talent and resources toward the realization of the most meritorious proposals. The second model of a single repository of innovation suffers all the flaws identified by Manz and Sims, described above.

These two models, however, represent two extremes, failing to recognize the hybrids that exist in the expanse between them. But it does note the difficulty associated with adopting Buckingham’s model with hiring and promotion. Under the first scenario, it must be understood that innovative minds are not so readily found in the marketplace as to allow population of an entire organization with them. Additionally, innovation is not a readily teachable set of traits and capabilities; although, there are a number of advocated products and approaches in the marketplace (such as Edward DeBono’s “Lateral Thinking,” and text by the same name). Under the second scenario, it would be necessary to hire an abundance of stellar-performing non-innovating workers to carry out the innovator’s vision. The problem with this approach is that it places too much work on the innovator, just as the non-delegating Type-A manager will typically rise to one level beyond his competence (unless learning to delegate effectively). This, of course, is the definition of the “Peter Principle.”

A hybrid model between these two extremes would have the Director of Human Resources hiring creative minds for a skunk works of innovation, on the one hand, and hiring a production workforce of exceptional executors, on the other hand. This was a model used most effectively by Thomas Edison, and, more recently, by Dean Kamens‘ DEKA Corporation. Both represent historical superlatives – i.e., that which has been rarely achieved. For every Bell Labs, Xerox R&D, IBM, and 3M of yesteryear, there are an abundance of the opposite examples. With each of these superlative examples (i.e., Bell Labs, etc.), they were particularly adept at innovating new products and deploying the necessary capital and resources to bring them to market. Their rarity, however, indicates the difficulty of bringing this to fruition, and the realization that none are currently considered among the most innovative organizations today indicates the difficulty in sustaining a culture of innovation and practical creativity over the long-term.

The reason for this is largely explained in Clayton Christensen’s “The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail.” As Christensen recounts with example after example drawn from various industries (but focusing on the disk drive industry), it is not the organization that innovates and employs capital and resources toward the realization of those innovations, it is the customer that drives the organization’s focus. This may seem contrary to intuition, but the reality is that organizations tend to focus on the demands of their existent customers – doing that which is most likely to satisfy the present source of their revenue streams. They are, on the other hand, unlikely to deploy significant resources servicing the creation and cultivation of new, innovative products for which an established market demand is not evidently available.

This, of course, does not mean that an organization cannot attempt to break this mold. When making the attempt, however, the immediate crisis of the moment tends to urge pulling away those working on the new, innovative project and deploying them toward resolution of the existing customer’s crisis. According to Christensen, the only model that works in the creation of novel innovations by established firms is for the existing corporation to create a standalone operation designed to bring a given innovation to completion. This would include separate staff, separate facilities, separate resources, and separate capital. None of these can be co-located or within the purview of the existing organization; otherwise, any of these may be redeployed when the need arises – and it predictably will.

It must, as well, be recognized that disruptive technologies and innovations tend to target a separate and greatly different customer base than the firm’s traditional clients, and that the newly- targeted market is likely to be smaller and less lucrative during the early stages of the new market’s lifecycle. Therefore, management is on less than solid ground when justifying deployment of the capital and resources toward such a new innovation. If the firm is public, with stock traded on an exchange, shareholders are likely to question the wisdom of investing significant capital toward a smaller market and an unproven product. Moreover, the net effect may promote what Peter Lynch describes in “One Up on Wallstreet” as “DeWorsification” – product diversification that extends beyond the firm’s established core competencies.

None of this undermines the utility of an organization encouraging innovation toward the improvement of an existing product and, thereby, satisfying existing customers or markets. Senior management can readily justify deployment of seed capital and resources toward the next advance. In this case, however, we have all the negatives associated with seeking a quantum leap improvement, identified by Edwards Deming and the other supporters of Total Quality Management. Specifically, quantum leap advances tend to promote increased variation in product reliability. While customers are typically willing to accommodate a certain level of frustration related to new product reliability, they are rarely willing to do so with established products. In the early days of personal computers, system crashes were common, but buyers accepted it because no suitable alternative existed and there was tacit recognition that computers were on the leading edge of technology. Today, however, the customer is unlikely to accommodate an increase in computer instability, even if the new computer is faster or unreliably does everything but birth babies, wash windows, and shear sheep.

Fortunately, we have the arrival of Six Sigma and LEAN Systems (courtesy of Genechi Taguchi and Toyota) as a model for installing incremental advances representing new innovation for existing products. This approach, however, requires enormous focus and tremendous engineering precision at the initial design stage – deploying the quantitative tools described at the National Institutes of Science and Technology (NIST) website. This level of precision focus, however, is largely an anathema for creative minds. This is why Apple and Google are so rare in the marketplace. Today, they are uniquely able to combine the creativity of innovation with the technological rigor of a quant geek. To a more limited extent, we see this uncommon combination in the gaming industry, but writing software code in the creation of the next videogame is a significantly less complex proposition than moving from Walkman to iPod, room-sized computer systems to Macintosh, creating an entire desktop environment of web-based tools, or Detroit’s efforts at inventing a moderately-priced hydrogen-powered car. [This is because software resides in the bits and bytes of programming code and requires no translation/transition to a factory and production operations to create the end product – it only requires transferring the code to a CD.] In each of the just-described advances, we have the example of quantum-leap innovation deployed toward the improvement of existing products – rather than invention of novel, never-seen-before products.

Ultimately, management consulting has cultivated a less than stellar reputation for itself. It is accused of installing solutions that are unsustainable after the consultant’s departure, shilling flavor-of-the-month management theories that will not withstand the test of time, and charging too much for too little improvement. In my view, establishing the position of Chief Innovations Officer threatens to sustain that reputation for all the reasons described above.

The “Secrets” of Good Management

A fellow academic who is preparing to teach a new management leadership course posted a question on LinkedIn recently. He wanted insights from experienced executives concerning the “secrets” of management. By this, he meant those items that are not typically taught in management school but strongly contribute to success, nevertheless. Here was my response, with a small number of revisions and extensions:

In an environment of international trade, this question becomes increasingly important because, both, opportunities and threats (the external portions of SWOT analysis) expand… significantly. Therefore, management training becomes all-the-more important, because executive competence is the only assurance of effectiveness in an increasingly competitive environment. To keep this short, I will assume that your students are already learning the standard tools and techniques of executive leadership and management (GE, BCG, SWOT, Factor Analysis, NPV, IRR, etc.) and will focus, instead, on the “secrets” that are infrequently taught.

First, we teach the concept of professional silos to note the importance of specialized expertise and the limitations of that expertise (i.e., “blinders” mentality). This is a recognition that was first put forward by John Kenneth Galbraith, who noted that specialization is a function of complexity. The concept of silos, however, urges recognition that coordination toward common objectives should be conducted, both, internal and with adjacent departments. This recognition is, both, true and limited, however.

On a sheet of paper write down the major management functions in a circle – strategic management, financial management, accounting, operations, marketing, information technology, legal, etc. Draw a line between those that have a logical connection, where a decision in one will impact another. If you think about this at depth, you’ll end up with lines connecting every functional area, and if arrows drawn at the ends indicate the direction of the impact, every line will have an arrow at both ends. This means that the level of communication and coordination necessary to achieve competent management require significantly greater focus, attention to detail and, indeed, coordination and communication than is often the norm in modern management.

Second, competent managers train their teams to be self-sustaining and self-functioning, and then they delegate. Delegation is not just a time management tool, it is the means by which to tap into the intelligence, creativity, and expertise of the front line experts. The manager who cannot delegate is the one for whom the “Peter Principle” was created. At some level in the organizational hierarchy, the occupant of the position cannot perform the work of every subordinate. At that point, this manager has risen to one level beyond his or her competence … unless able to delegate.

Two concepts from Walt Ulmer inform this second point. First, “power down, not power off” recognizes the leadership requirement to monitor, supervise, and support that which is delegated. A manager may delegate authority but not responsibility. The second concept is “the freedom to fail,” because learning is accomplished through success and failure, alike, and success is guaranteed to none of us.

Third, over 80% of problems in the workplace are attributable to management decisions and actions. Poor performance at the frontline is commonly attributable to inadequate training, inept leadership, a lack of managerial trust, insufficient funds, inadequate time, poor systems and processes, or a failure to plan, coordinate, and communicate. All are the responsibility of management. This was, perhaps, the most important contribution of Edwards Deming, who concluded from this that quality or its absence follows from management.

What Deming did not emphasize as strongly is the recognition that, if management is responsible for 80 percent of poor quality, 20 percent remains unaccounted. We may assume that this represents the non-management portion (i.e., frontline staff), but that would be a mistake. Just as Deming extended the work of Walter Shewhart in noting that product quality variation can be divided between assignable and unassignable causes, we may similarly segregate the remaining 20 percent into these two categories. A portion of that 20 percent will be due to market forces, including changing customer preferences, new and unanticipated regulatory requirements, and competitor actions and influences. In other words, some portion of that remaining 20% will be attributable to neither management nor the workforce. Consequently, the frontline staff is responsible for less than 20 percent of poor quality, compared to management’s 80 percent. Toward the end of his life, Denning indicated that this 80 percent figure was a minimum, and that the average was closer to 90 percent. Consequently, it seeking to diagnose the source of a problem, simple statistical probability indicates that and management is best advised to look within.

Fourth, finally, and most importantly, the true measure of a manager’s success is the frequency with which subordinates are promoted and successful after their departure.

The News Cycle of Medical Malpractice

My posting on the untrained customer in healthcare was jointly published in my department’s blog, http://effectivehealthexecutive.wordpress.com, where reader Laura Sample offered an interesting comment concerning word-of-mouth marketing. Her comment, with my response, follows:

One Response to “The Untrained Customer in Health Care II”

- Laura Sample Says:

January 24, 2008 at 7:48 pm

Excellent article. I just finished reading a book by Fred Lee called “If Disney Ran Your Hospital – 9 1/2 Things You’d Do Differently” It discusses a lot of these similar issues relating to focusing on improving the patient’s experience as opposed to simply good quality healthcare. If they have a good experience – they are more likely to be very satisfied and have a story to tell others.

Laura, thank you.

You may be interested to know that, on average, disgruntled or angry customers tell 21 others about their experience, while satisfied customers tell just 7. This means that we must fully satisfy 3 for ever one we anger. And, at that ratio, the organization is just breaking even — neither declining nor advancing its reputation.

Sound daunting?

Well, those figures are for non-healthcare industries. With the exception of Hollywood, no other economic sector generates gawking and salacious interest the way healthcare does. Go to a party where a dissatisfied patient is describing her experience to a friend, and she will soon be surrounded with listeners. If the story is a good one, her audience will become her apostles in the retelling of it … and do so repeatedly.

If the story ends up in the press (the best PR professionals are plaintiff’s attorneys, by the way), we are off to the races with the original news report and an interminable series of follow-up articles.

The papers will cover the trial, to say nothing of the pre-trial proceedings. They will describe similar incidents in other communities as the context and excuse for sustaining public interest in our friend’s legal proceedings. There will invariably be a report on whether the rest of us are also at risk for a similar event.

If the national media picks up the story, there will be local stories about the how the tragedy warranted national media attention.

Weeks and weeks later, you will know the cycle of reporting is nearing an end when, after the man and woman on the street interviews have come and gone, the press reports on the opinions and fears of grade schoolers.

At that point the cycle will stop … Until the next malpractice case arrives, and our friend’s case receives repeated mention in the “background” portion of articles covering the new case.

Before your time and mine, the sexually salacious murder case of silent film star Fatty Arbuckle filled the press. Arbuckle was accused of accidentally killing his partner during an evening of unrestrained entertainment. Interestingly, Mr. Arbuckle was acquitted in less than 10 minutes, but only after several mistrials from deadlocked juries and substantiated allegations of witness tampering by the prosecution. In any event, Mr. Arbuckle died in June of 1933, but his name was repeatedly mentioned in the reporting of the Michael Jackson case – suggesting that a good news story is like the lifecycle of bellbottom blue jeans in that it never fully dies, it just goes into temporary remission.

And this is why publicists earn generous incomes, and reputation management is considered a viable sub-discipline of marketing and public relations. It also suggests that, over time, the expense of lost reputation is likely to equal or exceed the cost of the average malpractice jury award.

“Strategery” is More Than Just a Word — Strategic Management in Healthcare IV

As with any doctrine or tact, the devil is in the details, and the utility of the approach is only realized when exercised intelligently. Suggesting that you read an abundance of articles from around the country falls well short of the mark, if the goal is to provide a model for strategic decision-making. A local healthcare provider in Las Vegas may be noted for hiring Hooters waitresses to serve as greeters and valet parking attendants at the local hospital – indicating that customer satisfaction has increased significantly with an attendant climb in market share, even if male-patient falls in the facility portico have increased. Such an approach may not be a smart move for the local hospital in Mars Hill, NC, where church and God view managerial excellence differently.

Consequently, a single article describing this new approach is not sufficient to identify an actionable trend or solution. To do this, it would be necessary to consider local market economics, the influence of testosterone on customer purchasing decisions, and the likely level of tolerance by the local community — to say nothing of spouses. If, on the other hand, two or three small- and medium-market hospitals in different locations around the country have undertaken a similar strategy and realized similar benefits, it is more likely that you have identified an actionable trend.

More importantly, this early identification of a trend is only “actionable” in the sense that you have a choice to make – namely, do likewise, alter it to better fit the local environment, or affirmatively elect to pass up on this opportunity. Regardless, you have identified the trend before the New York Times and the first publication of a consultant’s white paper. And if the decision of whether or not to adopt the trend is a close call, you have identified it with sufficient time to consider the choice at depth. Too much of what constitutes executive decision-making is rendered quickly, under the pressures and imperatives of market competition.

In other words, there is nothing about this exercise that excuses management from exercising good judgment. My students and I, however, used this technique to predict many of the current and recent trends in health care – including, re-importation of medications, constraints on pharmaceutical marketing, the undermining of patent protection for novel therapeutics, and the arrival of health-savings plans and high-deductible plans, among many others. That initial exercise back in 1998 has rendered an estimated accuracy rate approaching 90%. Consequently, it may be worthy of your consideration as an executive leader in healthcare.

“Strategery” is More Than Just a Word — Strategic Management in Healthcare III

So, now we have the street address to Goliath’s home.

This is a positive? Absolutely.

It means that most of the constraints and challenges faced locally apply everywhere across the country. It means that every provider is seeking a solution to the same problems. It means that other institutional providers are compelled to attempt solutions (even if uncertain of its ultimate success). It means that, invariably, some institutional provider will identify a solution, even if attributable to nothing more visionary or sagacious than pure, dumb luck. And, strangely, it means that, in their success, they will advertise their good fortune and approach in an effort to advance their reputations (personally and institutionally) — in a quiet “see how smart we are” exercise.

It should be understood that no local institutional provider will likely advertise their success beyond the local market, where expansion of that reputation renders the greatest benefit. Consequently, it will take some time before their realized advance is described in the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, Time Magazine, Newsweek, or US News. Reading the local newspapers from around the country, as my students and I have done for years, therefore, represents a strategic advantage and source of strategic ideas for local executives. In fact, this is precisely what the consultants are doing, as they seek to identify the next “New-New” thing. Consultants, after all, are not that creative. During the span of an average career, none of us has more than five or six significant insights in us. Consultants are no different.

Reading the local newspapers from around the country, however, is problematic. No senior executive has such an abundance of available time. The requirements of the job and putting out the immediate fires that define day-to-day leadership make such an expectation impossible. But, if you could do so, you would identify trends before the consultants publish their “findings.”

There is, of course, a solution in the numerous online journal services available. They scan local newspapers nationwide for articles related to healthcare, public health, and health care policy, focusing on articles from not only the New York Times and Washington Post, but, even better, the Athens Banner Herald, The Raleigh News and Observer, and the Houston Chronicle, among many others. My personal favorite is the service at Healthleaders.com, which will send daily updates by e-mail. HealthLeaders focus on national and local healthcare, however, makes them better than similar services from CNN and most other major news outlets.

Ken Fisher recently published “The Only Three Questions That Count.” Throughout that marvelous book on investing, he makes the case for the power and effectiveness of information that the competition has not yet identified. The approach described above provides strategic leadership with the ability to do just that – identify that which the competition has not.

In the next, final posting on this topic, we will address the specifics of this approach and identify a secondary benefit that is nearly as important as the one just described.

(Continued)

“Strategery” is More Than Just a Word — Strategic Management in Healthcare II

Our goal is to identify actionable healthcare trends before the competition and, more importantly, before the consultants publish the first white paper in recognition of the trend. Why?

Well, once the first white paper is published, it will be purchased and shared throughout the industry – becoming common knowledge and informing the decisions of, both, your organization and the competition… simultaneously. In fact, one of the requirements of economic theory is the presence of instantaneous and perfect information. While this requirement was questionable in previous eras, today’s ready availability of information now gives it a greater ring of credibility than at any time previous.

Starting in 1998, my students and I began surveying the health-care-related articles in local newspapers from around the country. This followed the balanced budget act of 1997, and the significant financial constraints on health care providers that followed. Starting as early as 1985, with the arrival of DRG’s, the federal government began to more prominently influence the healthcare marketplace. The BBA of 1997 took this a quantum leap further. Together, they and their successors represent, both, a limitation and a potential opportunity for strategic management and planning.

Specifically, if a single, largely-dominant, external source now drives the industry, then power shifts, and the influence of even prominent healthcare leaders declines. Today, the primary force in healthcare is not Harvard, Hopkins, Columbia, or Duke. Nor is it the AMA, AHA, ACS, or Joint Commission. If we adopt Deep Throat’s admonition and follow the money, it leads us directly to DC – the home of HHS, Medicare, Medicaid, SCHIPs, the federal government’s health insurance offices for government employees, and the headquarters of the US Penal System, which oversees the healthcare delivery for the largest inmate population. Each, to one degree or another, is influenced by CMS – the creators of the CMS 1500 Form, off which the UB 92 is based (same codes, same fields, same source of reimbursement standards, just more convoluted). And CMS reimbursement standards are the basis on which much of conventional insurance is calculated. On the Medicaid side, CMS is in an unequal partnership with the states (lowering compensation over the last several years without the consent of the states). With the arrival of Medicare-Advantage and the Medicaid equivalents, CMS even drives the process of revenue streams for this public / private partnership. For the practitioner and institutional provider, these are the limitations or negatives, because they create a de facto reimbursement monopoly.

The opportunity, in theory, is that change is now largely driven by a single source. We know from whence it comes, where it lives, what motivates it, what food it prefers, and even its preference in mates, We know the pace with which each is likely to change over time (i.e., the election cycles plus a lag for legislative enactment). With few exceptions, we understand the Newtonian physics that govern the planet on which it resides – a world that is marginally different from our own.

This includes whether an object (healthcare bill) in motion tends to stay in motion, unless acted upon by an external force [it does]. Whether force equals velocity (political clout) multiplied by mass (public sentiment) [it does]. Whether for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction [it does not – the reactions tend to be stronger]. And we know the gravitational forces, even if unable to calculate them precisely – which is the gravitational constant, of healthcosts x public sentiment, divided by the square root of the distance between the two political parties. Think of this as the Philosophia Naturalis Principia Mathematica of healthcare.

Best of all, we know that the results apply to all similarly-situated providers and organizations with reasonably consistent uniformity. Consequently, as the largest payer in the healthcare universe, we could predict as early as 1997 that CMS would constitute the primary source of, either, health care change or stability.

This, in fact, is precisely what has happened. Indeed, managed-care reimbursement is now based on a percentage of CMS compensation levels, core measures and outcomes reporting has been driven by CMS, as well, and the lion share of other significant initiatives within the industry now originate there or enjoy its consent. This, of course, may be viewed as a negative, because it limits flexibility, undermines free-market forces, eliminates competitive advantages (as each provider scrambles to comply), and gives the local healthcare leadership an unavoidable sense that they are no longer the captains of their ship.

But it does provide an unexpected and actionable positive – which we will address next.