Posts Tagged ‘Health policy’

California: The Problem in a Nut Shell — The Looming Crisis of Healthcare

The rising and unsustainable cost of health care inflation has prompted cutbacks in state funding of Medicaid in an assortment of states across the nation. I know this directly from my work with the government in Pennsylvania, and news reports from papers around the country indicate a similar experience. Yesterday, the state of California elected against pursuing Governor Schwarzenegger’s new health-care initiative – a modification of the approach undertaken in Massachusetts. Interestingly, a student in our executive program was one of the authors of this initiative. More interesting, still, a day later the state insurance commissioner vowed to strictly enforce the compensation laws, following a study indicating improperly denied and delayed payments by insurance firms.

Back in 1998, with my first quality improvement class, my students and I came up with a model for health care that has proven remarkably accurate. One of the items in that model was the recognition that the capacity constraints challenges that prompted the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 would only grow increasingly worse as the boomer generation approached retirement. We predicted then that the inveterate cost-shifting between insurance and government-sponsored payers, which prompted the arrival of DRGs, the failed Clinton health-care plan of 1993, and the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, would increase in intensity – pitting government against the insurance industry. This is based on the realization that we were approaching the limit of cost reduction and efficiency improvements available to practitioners. Unable to squeeze practitioners further, finger-pointing between payers seemed a likely act of desperation. http://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-bonus30jan30,1,4329899.story?ctrack=1&cset=true This, however, was not the limit of our predictions with respect to health care insurance. We foresaw the arrival of high deductible plans, as a means of cherry picking those least in need of medical care. With subsequent classes, we became increasingly concerned that such plans would promote the death spiral of adverse selection for the insurance industry.

While a subscription is required to this Wall Street Journal article, the freely available introduction notes two tangent issues with the California initiative and its defeat. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB120165305949826973.html?mod=hps_us_at_glance_health .

The first item is the recognition that California represented a poor prospect for a Massachusetts-style initiative, due to the size of its indigent and uninsured population. The Massachusetts initiative requires health care insurance coverage by all who are financially able to afford it, while promising state coverage for those who are not. Given the size of California’s indigent population, the defeat of this proposal is understandable. This, however, suggests that relying on state initiatives represents an unlikely solution to the looming resource constraints crisis, because California is not the only state with a significant indigent and uninsured population.

The second item mentioned in this introduction is the recognition that the California initiative (like that in Massachusetts) does nothing to address the core causes for health care inflation. In fact, no initiative of which I’m aware directly determines the most significant drivers of health care inflation, much less attempt to constrain them.

Constrain them? Isn’t that the rightful role of the free market?

Absolutely, but healthcare is not a free market, where competition serves to increase quality while managing cost to the customer. Medicare, Medicaid, SCHIPS, state and federal coverage for government workers, local government contributions to augment indigent care, federal coverage of black lung and other special forms of workers’ comp cases, and government coverage of healthcare for the prison population, combined, exceed all other payer classes and account for more than 50 percent of healthcare payments in the US. Consequently, healthcare in the US is more akin to socialized medicine than a free market. And this has contributed the problems described above — an unintended consequence of the effort to do the right thing when Medicare and Medicaid were introduced in 1965.

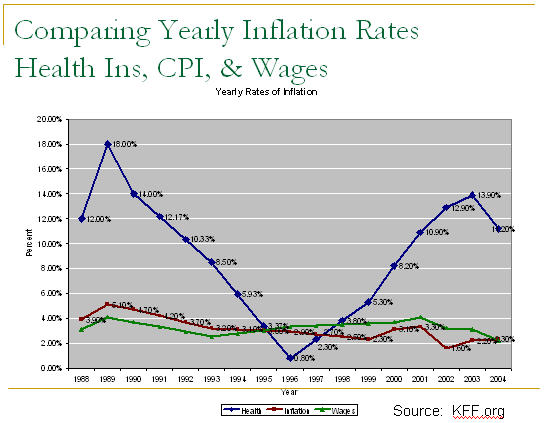

To graphically demonstrate the problem, here is a chart showing the year-over-year inflation rate of health care (blue line) in comparison to inflation within the United States (red line) and wage inflation (green line) from 1989 to 2004.

The previous chart, which indicates the yearly disparity between health-care inflation and wage inflation (the capacity of our customer to purchase our services), fails to provide a sense of the accumulated problem over time. Therefore, it is necessary to index each to 1989, in order to identify the cumulated effect.

The next chart, which extends back to 1981, indicates that, if health-care costs were held steady for the foreseeable future while wage inflation continued to grow along a regressionary trendline, it would take 61 years for wage inflation to catch up.

It is worth noting that the coefficient of determination (r-squared) for the wage trend line is greater than 0.99.

This is the problem we face. It is the reason government and the insurance industry seek to reduce payment to practitioners on a yearly basis. It is the reason the American people list rising healthcare costs as a significant political issue when they vote. And, surprisingly, no initiative by government has sought to identify and address the core drivers of health-care inflation. Less surprising, but disconcerting, nevertheless, no organization within healthcare has sought to do that which government has avoided.

Is it too late to address the problem? Well, the Boomer generation starts retiring in less than two years (some have already started early retirement). Our 45 million seniors of today will grow to more than 80 million by 2030, and Medicare is slated to go bankrupt by 2020. So, I’m not very optimistic. But I am open to your suggestions.

Related stories:

California Governor vows to continue effort: http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2008/01/30/MNHIUOK24.DTL&hw=Bill+%27over%27&sn=001&sc=1000

Article describing the defeat of the California proposal: http://www.latimes.com/news/local/la-me-health29jan29,1,1860303.story?ctrack=2&cset=true

Cost of Massachusetts plan expected to grow beyond $400 million: http://www.boston.com/news/local/articles/2008/01/24/cost_of_health_initiative_up_400m/